The book examines the effects of volatility in higher state funding

[ad_1]

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — With inflation running rampant and some financial experts predicting an economic recession in the US this year, officials at secondary education institutions – and families attending college – have reason to worry, as a faltering economy often signals cuts to higher education funding, researchers say in a new book .

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — With inflation running rampant and some financial experts predicting an economic recession in the US this year, officials at secondary education institutions – and families attending college – have reason to worry, as a faltering economy often signals cuts to higher education funding, researchers say in a new book .

Experts in higher education, public policy, and other disciplines examine the implications of the initiative in state allocations to higher education and explore possible solutions in the new book “State Expenditure Volatility for Higher Education,” published by the American Educational Research Association and released at the conference. recently in Chicago.

During recessions and other economic downturns, state funding for higher education is particularly vulnerable as it is the second-largest or second-largest category of discretionary spending, averaging about 9.6% of the state budget, said the book’s editor Jennifer Delaney, a professor of education policy. organization and leadership at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

“With the exception of Vermont, every state also has a balanced budget mandate, so when we have a downturn, higher education spending is almost always cut,” said Delaney. “Right now, higher education is still benefiting from COVID-19 relief funds, and when that dries up, many states will face a financial precipice for higher education.”

Studies by various experts in this volume examine how volatility in state funding affects the affordability of colleges through increases in tuition fees, graduation rates, and institutional decisions such as hiring contingent instructors rather than tenured professors.

With colleges and universities under increasing pressure to find predictable revenue streams to shore up their budgets, there is the potential for a toll on public goods, Delaney said.

“Institutions are more likely to start MBA programs that generate income than to develop them in the humanities that support an important social good, such as teacher training,” said Delaney. “Uncertainty in state budgeting is changing the nature of what public institutions do and changing it in ways that are likely to undermine the contribution that education makes to society and democratization – and that is not usually the direction states expect. We should worry about that.”

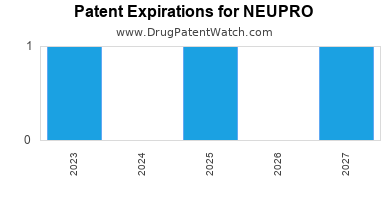

A study in the book by Delaney and co-author William R. Doyle, a professor of higher education and public policy at Vanderbilt University, looked at the length of time it takes for higher education funding to return to previous levels when state allocations are cut.

In the past, institutional leaders may have hoped that their state revenues would recover quickly, and they could implement temporary measures such as limiting travel and increasing salaries and temporarily suspending maintenance of campus buildings. However, “it has become clear in many states that this approach is no longer sufficient,” write Delaney and Doyle. “It takes longer and longer to recover from the cuts, if recovery comes at all.”

They see cuts of 1%, 3%, 5% and 10% in state allocations to higher education over the period 1984-2015. They chose that period because it included the Great Recession but excluded the economic downturn triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic.

During the 1980s, cuts of 5% or less were rare, and “most states — about 75% — returned higher education funding to previous levels within four years,” says Delaney. “But in the 1990s, of the 41 states that cut higher education allocations, only 45% recovered those funds within six years. And recently – from 2000-2015 – recovery has become even more unlikely. Only 5% of the states in the risk pool had state revenues restored to their previous levels in five years.”

Countries with higher levels of financial assistance recovered post-secondary funds more quickly, researchers found, while recovery took the longest in Southern and Western states and in states with higher tuition fees at colleges and universities. their country.

Dramatic fluctuations in state income and rising costs of attendance not only affect access, but can change a student’s choice of majors, prompting students to choose a major with higher earning potential to repay their loan debt than a paying field such as education or social work. lacking but beneficial to the public interest, Delaney said.

When weighing the politically unfavorable consequences of reducing funding for higher education and the politically unfavorable prospect of raising taxes, state leaders are left to seek alternative sources of revenue, the authors say. With these limited resources, some scholars have suggested allocating state lottery revenues towards higher education.

An in-book study by researchers Christopher R. Marsicano of Davidson College, Jenna W. Kramer of the RAND Corporation and Steven Pittenger Gentile of the Tennessee Commission on Higher Education examined 25 years of data on lottery allocations to higher education and their effect on state allocations. Concluding that the effect on volatility is “largely nil”, the group cautioned, however, that lottery allocation and revenue are finite resources that are “not a silver bullet to sustain funding uncertainty.”

Also among the alternative financing mechanisms examined by the scholars in this book are countercyclical sources such as the formation of federal-state partnerships. Other researchers examine whether state financial policies protect higher education funding from uncertainty, investigate whether the gender composition and political affiliation of governors and lawmakers influence allocations and explore potential links between states’ economic performance and their higher education subsidies.

Although the COVID-19 pandemic is waning, the resulting economic chaos has exacerbated volatility and depleted the resources needed to serve vulnerable student populations, increasing the risk of them not completing their degree, Delaney wrote.

“Volatility is likely to remain an enduring issue or ‘nasty problem’ that requires dedicated and creative minds to manage and research,” he said. “But it has the potential to be scaled up through carefully crafted public policies. Emphasizing the stability of funding is important, especially considering the public good that higher education generates.”

[ad_2]

Source link