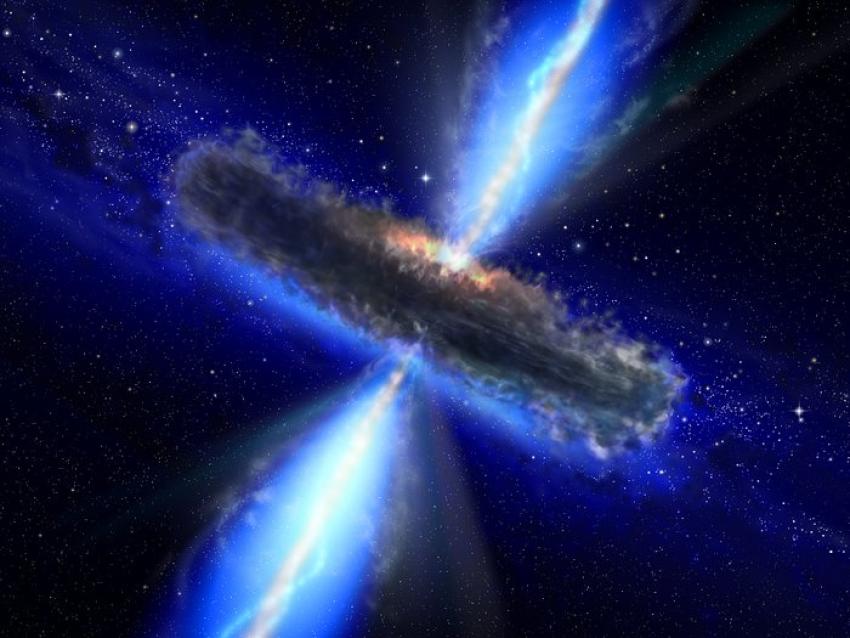

A hidden supermassive black hole powered by colliding galaxies

[ad_1]

(Nanowerk News) Astronomers have found that supermassive black holes obscured by dust are more likely to grow and release large amounts of energy when inside a galaxy that is expected to collide with a neighboring galaxy. The new work, led by researchers from the University of Newcastle, is published in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society (“Unclear AGN enhancement in galactic pairs at cosmic midday: evidence from the probabilistic handling of photometric redshift”).

Galaxies, including our Milky Way, contain supermassive black holes at their centers. They have a mass equivalent to millions, or even billions, of our Sun’s. This black hole grows by ‘eating’ gas that falls on it. However, what pushed the gas close enough to the black hole for this to happen is an ongoing mystery.

One possibility is that when galaxies are close enough to each other, they tend to be gravitationally attracted to one another and ‘merge’ into one larger galaxy.

In the final stage of its journey to the black hole, the gas ignites and releases a large amount of energy. This energy is usually detected using visible light or X-rays. However, the astronomers who carried out this study were only able to detect the growing black hole using infrared light. The team used data from a variety of telescopes, including the Hubble Space Telescope and the infrared Spitzer Space Telescope.

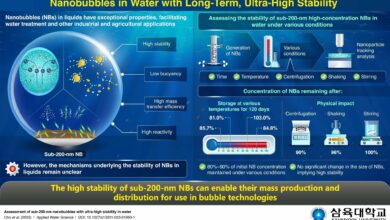

Researchers developed a new technique to determine how likely it is that two galaxies are very close together and are expected to collide in the future. They applied the new method to hundreds of thousands of galaxies in the distant universe (looking at galaxies that formed 2 to 6 billion years after the Big Bang) in an effort to better understand what’s called the ‘cosmic day’, when most of the Universe’s galaxies and black holes grow. is thought to have occurred.

Understanding how black holes grow over time is fundamental to modern galaxy research, especially because it can give us insight into the supermassive black holes that lie within the Milky Way, and how our galaxy has evolved over time.

Due to their great distance, only a small number of cosmic day galaxies meet the necessary criteria for accurate distance measurements. This makes it very difficult to know with high precision whether two galaxies are very close to each other.

This study presents a new statistical method to overcome previous limitations in accurately measuring the distances of galaxies and supermassive black holes during the cosmic day. It applies a statistical approach to determining galaxy distances using images at different wavelengths and eliminates the need for spectroscopic distance measurements for each individual galaxy.

Data coming from the James Webb Space Telescope over the next few years is expected to revolutionize research in the infrared and reveal more secrets about how these dusty black holes grow.

Sean Dougherty, a graduate student at Newcastle University and lead author of the paper, said, “Our new approach looks at hundreds of thousands of distant galaxies with a statistical approach and asks how likely it is that two galaxies are close together and how likely it is. on a crash course.”

Dr Chris Harrison, one of the study’s authors, “These supermassive black holes are extremely difficult to find because the X-ray light, which astronomers normally use to find these growing black holes, is blocked and undetectable by our telescopes. But these same black holes can be found using infrared light, which is generated by the hot dust that surrounds them.”

He added, “The difficulty in finding this black hole and in establishing precise measurements of its distance explains why these results have previously been challenging to pinpoint these distant ‘cosmic day’ galaxies. With JWST we hope to find more of these hidden growing black holes. JWST will be much better at finding them, therefore we will have a lot more to learn, including the hardest to find ones. From there, we can do more to understand the dust that surrounds it, and find out how much of it is hidden in distant galaxies.”

[ad_2]

Source link