The new treatment regimen appears to be well tolerated, benefiting children with

[ad_1]

AGUSTA, Ga. (April 25, 2023) – First in-human study of a new immunotherapy that blocks a natural enzyme tumor commander for their protection is well tolerated by children with recurrent brain tumors and allows many people to live the unpredictable months of different lives more normal, the researchers said.

AGUSTA, Ga. (April 25, 2023) – First in-human study of a new immunotherapy that blocks a natural enzyme tumor commander for their protection is well tolerated by children with recurrent brain tumors and allows many people to live the unpredictable months of different lives more normal, the researchers said.

“Our children are generally out of the hospital and going about their daily activities. They go to school, we have college young adults who live in their own dorms, take their own medication and come to see us about once a month,” says Theodore S. Johnson, MD/PhD, pediatric hematologist/oncologist and co-director of the Pediatric Immunotherapy Program. at Georgia Children’s Hospital and Georgia Cancer Center.

A phase 1 trial of indoximod plus chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy began in 2015 at CHOG and Children’s Hospital of Atlanta. The researchers enrolled 81 children ages 3 to 21 from across the country with all types of brain tumors that recur or never heal, called developmental. Around the middle of the trial, the researchers added children newly diagnosed with a rare aggressive diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma, or DIPG, which cannot be treated with surgery and for which no treatment is currently considered curative.

Johnson presented a five-year analysis of safety, tolerability, and results from a phase 1 trial during the American Academy of Neurology Annual Meeting April 22-27 in Boston.

Indoximod inhibits IDO, or indoleamine 2,3 dioxygenase, an enzyme that fetuses and brain tumors use to hide from the immune system. IDO inhibitors help prevent tumors from using IDO to suppress the immune system’s natural response to invaders such as tumors. Johnson notes that SSI inhibitors don’t work alone, but rather, experimentally, in combination with chemotherapy, radiation or targeted therapy, which target the molecular mechanisms tumors use to grow.

Assessing the safety and optimal dose of indoximod is a key endpoint of this and other phase 1 trials, Johnson noted. Follow-up phase 2 trials focused on efficacy and partially funded by the National Cancer Institute have been conducted again at CHOG and CHOA, as well as Cincinnati Children’s Hospital and Dana Farber Cancer Institute in Boston.

While the majority of children in the phase 1 trial experienced some side effects such as vomiting and anemia, most of the side effects were mild; Most serious side effects, including heart attacks and strokes, are directly attributable to the development of brain tumors, Johnson and his colleagues report.

They approach research by prioritizing the quality of life of children. “We structured the treatment so the chemo wasn’t too intense, and it was all oral chemo,” said Johnson. “It’s not the same intensity as high-dose intravenous regimens that drive a lot of severe side effects and very low blood counts that make you need transfusions, make you susceptible to infection and land you in the hospital for infections and stuff.”

Some of the young patients in the first phase of the trial were already taking temozolomide, a chemotherapy drug commonly prescribed for brain tumors, and their tumors progressed. But adding an SSI inhibitor to their regimen created a whole new treatment, said Johnson.

“It helps activate the immune system. Combinations seem to be better because you’re hitting the tumor with drugs with different mechanisms of action,” said Johnson, a common approach in cancer treatment today. “And, of course, the idea of SSI-inhibiting therapy is that we hope to unleash a stronger immune response.”

Researchers are still analyzing and planning to publish laboratory findings on the overall immune response of the treatment regimen. Detailed, high-throughput immune testing in DIPG patients showed a marked increase in the activity of immune cells called T cells, a key driver of the immune response, after undergoing treatment that included an IDO inhibitor-based therapy.

The median survival time in the trial was 13.6 months, whereas the median survival for children with relapse with the types of brain tumors included in this study was about six months, according to the most recent literature. Some of the study patients were alive five years after the study, Johnson said, and one was still undergoing therapy.

Children with DIPG had a median survival of 14.4 months, said Johnson. Most children with DIPG are diagnosed before age 7 and live about 9 to 11 months after diagnosis. Due to the small number of children with DIPG enrolled, the results cannot be considered statistically significant, meaning a clear correlation between treatment and survival time cannot be established for DIPG patients.

“Response patterns for study participants ranged from tumors growing relentlessly with some children not even getting a second cycle of treatment to children who soon had tumors that shrunk that remained missing for a period of time,” Johnson said. He notes that stabilizing only one of these tumors is important because tumors that grow in the brain want to continue growing, which can damage your nervous system, robbing you of basic functions such as the ability to walk, speak, and swallow. Some patients in studies recovered this basic ability over time.

For this trial, the researchers didn’t draw hard lines about when treatment should be stopped. Children stay on medication as long as it is beneficial, and as long as their symptoms clear up. Some children, for example, eventually lose the ability to swallow, which is essential for taking pills. Those late-stage type symptoms suggest that the tumor is putting pressure on important parts of the brain making any treatment problematic, he said. But overall survival rates were better than expected for late-stage relapsed tumors, he repeated.

The study also has the flexibility to switch chemotherapy drugs as needed if the tumor becomes resistant, which is called adaptive management, and this allows patients to continue immunotherapy. They had 18 patients who were switched to alternative chemotherapy regimens plus indoximod and the median overall survival for that group was 34.7 months.

“Switching chemotherapeutics definitely had an impact on that group but needs to be studied in more detail,” said Johnson, with more patients with the same type of tumor — the goal of an ongoing phase 2 study — to make sure they don’t. happened to get a patient who was very sensitive to the second chemotherapy regimen.

Cancers can also become resistant to immunotherapy, which is why researchers began to look for other immunotherapies with a different pathway of action than indoximod. That led to a new phase 1 trial, which paired indoximod with a second immunotherapy drug ibrutinib plus chemotherapy. “We thought it would amplify the immune effect synergistically,” Johnson said.

Palliative radiation, surgery or the corticosteroid dexamethasone, which can be used to treat fluid buildup in the brain, are also permitted according to the patient’s needs.

Overall the phase 1 trials were “absolutely” successful, Johnson said, noting that while pediatric phase 1 trials are usually difficult to recruit because they can enroll a target of 81 children in three years. In addition, most of the phase 1 trials did not have sufficient findings to support the transition to phase 2.

“The phase 1 trial fulfilled its goal of delivering the treatment safely, proving that treatment in combination with chemotherapy and radiation is feasible and in determining the best and safe dose of indoximod for the two combinations,” Johnson said.

David Munn, MD, a Johnson colleague who is co-director of the Pediatric Immunotherapy Program, was part of the team that reported in 1998 in the journal Science that the placenta expresses IDO to help protect the fetus, which has DNA from both parents, from the mother’s immune response. MCG researchers would later discover that tumors induce SSI as well, most likely from the immune system itself, which produces enzymes as part of its natural checks and balances.

Brain tumors are the most common tumors in children and leukemia is the most common cancer, according to the American Cancer Society.

Other types of tumors in the phase 1 trial include ependymoma, a tumor that begins in the cells lining the cerebrospinal fluid passages in the brain and spinal cord; medulloblastoma, which tends to start at the base of the brain and spread to other areas of the brain and spinal cord; and glioblastoma, a fast-growing tumor that develops in the brain cells that support neurons.

Johnson and Munn are also currently working with Dr. Rafal Pacholczyk, director of the Joint Immune Monitoring Laboratory at the Georgia Cancer Center, in developing a flow cytometry test that will show how the immune system responds to an immunotherapy regimen. Tests could be performed more quickly and ideally less expensive in the future so that the results can be used to monitor and/or change child care programs in real time. The in-depth sequencing study they have performed on patients in the phase 1 trial will help identify markers for the new flow cytometry test.

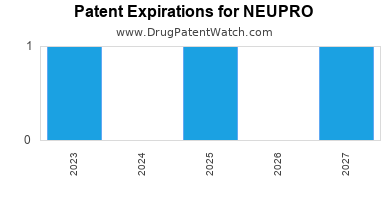

Augusta University holds the patent for the SSI inhibitor drug indoximod. Lumos Pharma, Inc. (formerly NewLink Genetics Corp.), a biopharmaceutical company based in Austin, Texas and Ames, Iowa, is producing the drug and partially funding phase 1 clinical trials.

Munn and Johnson are also scientists affiliated with MCG’s Immunology Center of Georgia.

For more information about the study, contact Taylor King, nurse navigator, at 706-721-2949 or (email protected)

Research methods

Randomized controlled/clinical trial

Research Subjects

People

Article title

Indoximod Pediatric Trial With Chemotherapy and Radiation for Recurrent Brain Tumor or Newly Diagnosed DIPG

Article Publication Date

12-Apr-2023

[ad_2]

Source link